“Mastery follows the body’s own design—a spiral path where movement, joy, and resilience grow together.”

I see, over the years, where I got confused between refinement, mastery, and erasure. It’s in my nature to want to get better at something. I once believed this was purely a “good” quality, but now—after years of running behind the mail truck—I see the anxiety that distracts from true being.

Daniel Seillier, the man who taught me to be both an artist and a man, used to say that going through the process was enough, and that refinement would come in time. I wish I had listened better and trusted more in the joy of dancing to grow the mastery I longed for—not just mastery of the art form, but of life itself.

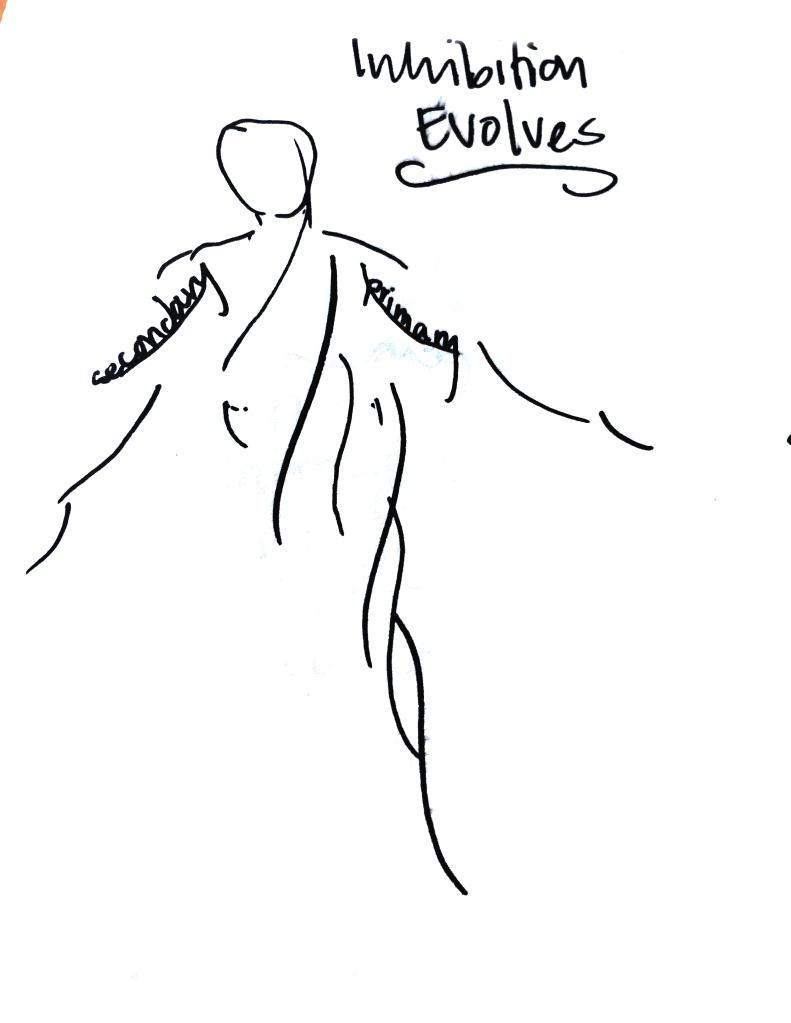

Mastery has acquired an elitist reputation, as if it demands one perfect way, one perfect body, in one perfect situation. But true mastery is a quiet adaptability to any circumstance, using whatever is at hand. It’s about resilience, not static perfection (if such a thing even exists).

Mastery doesn’t arrive on command, and it must keep evolving, pulled forward by desire and deep love for the subject. It is deeply personal. That’s why it’s crucial to notice when love wanes, or when the chase for mastery overshadows joy. This joy is not the loud, fleeting rush of social media validation, but a quiet joy—one that lets you breathe freely, see with fresh eyes, and move without strain.

Alex Murray often reminded us that we work from the approximate toward the refined. To try to “master” something directly is impossible, no matter how many repetitions you do. Watch a horse galloping, an athlete competing, or a child playing: theorizing about their movement and imposing your own ideas won’t help.

I see many people trying to walk, run, swim—or even sit in meditation—“straight,” refining something that is inherently spiraling by nature, stripping away the curves that make it whole. This is not refinement—it’s erasure. In scrubbing away our body’s innate movement patterns to fit a model, we lose joy and unwittingly force the body into a performance of mastery, hoping the real thing will follow.

When I visited a Buddhist monastery twenty-some years ago, I asked the abbot if he knew about Alexander Technique teachers. He smiled and said that yes, occasionally they came to the monastery to sit very straight. The implication was clear: “straight” is not the same as wise. I’ve thought about this a lot over the years.

Since then, I’ve had to remind myself constantly—in dance and in life—to stop erasing and start allowing. It requires presence, and it supports the joy inherent in being a unique mover in the world.

Joy lives in the spirals. Let them carry you—into movement, into resilience, into life.

El Camino en Espiral hacia la Maestría

“La maestría sigue el propio diseño del cuerpo: un camino en espiral donde el movimiento, la alegría y la resiliencia crecen juntos.”

Con los años me he dado cuenta de cómo me confundí entre refinamiento, maestría y borrado. Es parte de mi naturaleza querer mejorar en algo. Antes creía que esto era puramente una cualidad “buena”, pero ahora—después de años corriendo detrás del camión del correo—veo la ansiedad que me distrae del verdadero ser.

Daniel Seillier, el hombre que me enseñó a ser tanto artista como persona, solía decir que atravesar el proceso era suficiente y que el refinamiento llegaría con el tiempo. Ojalá hubiera escuchado mejor y confiado más en la alegría de bailar para cultivar la maestría que anhelaba—no solo la maestría del arte, sino de la vida misma.

La maestría ha adquirido una reputación elitista, como si exigiera un único camino perfecto, un cuerpo perfecto y una situación perfecta. Pero la verdadera maestría es una tranquila capacidad de adaptación a cualquier circunstancia, usando lo que se tenga a mano. Se trata de resiliencia, no de perfección estática (si es que tal cosa existe).

La maestría no llega por mandato, y debe seguir evolucionando, impulsada por el deseo y el profundo amor por el tema. Es profundamente personal. Por eso es crucial notar cuando el amor se desvanece o cuando la persecución de la maestría eclipsa la alegría. Esta alegría no es el estímulo ruidoso y efímero de la validación en las redes sociales, sino una alegría silenciosa—la que te permite respirar libremente, ver con ojos nuevos y moverte sin tensión.

Alex Murray solía recordarnos que trabajamos desde lo aproximado hacia lo refinado. Intentar “dominar” algo directamente es imposible, sin importar cuántas repeticiones hagas. Observa a un caballo galopando, a un atleta compitiendo o a un niño jugando: teorizar sobre su movimiento e imponer tus propias ideas no servirá de nada.

Veo a muchas personas intentando caminar, correr, nadar—o incluso sentarse a meditar—“rectos”, refinando algo que es por naturaleza espiral, eliminando las curvas que lo hacen completo. Esto no es refinamiento, es borrado. Al eliminar los patrones de movimiento innatos del cuerpo para encajar en un modelo, perdemos la alegría y, sin darnos cuenta, forzamos al cuerpo a una representación de la maestría, esperando que la verdadera llegue después.

Cuando visité un monasterio budista hace unos veinte años, le pregunté al abad si conocía a los profesores de Técnica Alexander. Sonrió y dijo que sí, que a veces venían al monasterio a sentarse muy rectos. La implicación era clara: “recto” no es lo mismo que sabio. He pensado mucho en esto a lo largo de los años.

Desde entonces, me recuerdo constantemente—aunque sea en la danza o en la vida—que debo dejar de borrar y empezar a permitir. Requiere presencia y sostiene la alegría inherente de ser un ser único en movimiento en el mundo.

La alegría vive en las espirales. Déjalas llevarte—al movimiento, a la resiliencia, a la vida.